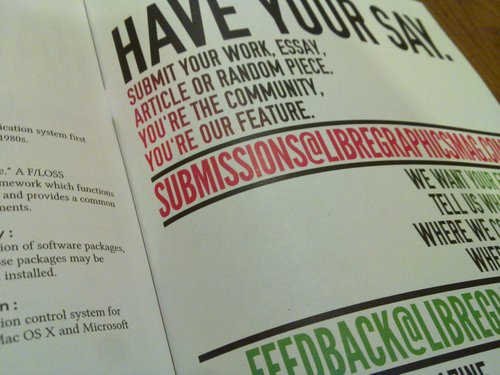

It's not up on the Libre Graphics magazine site yet, but it will be soon. In the mean time, bask in the insiderness of seeing this call for submissions on its first day in the wild.

Libre Graphics magazine issue 1.2: Use Cases and Affordances

Use cases, at their core, are about the way users proceed through a system in order to achieve an outcome. Normally, there are lots of diagrams and small details involved in creating a use case. But we're not here to go over technical detail. Instead, we're here to talk about that core, the idea of looking at paths of use and interaction.

Then there are affordances, the features of a thing, its possibilities, the ways in which it might come to be used.

Clearly, then, we're talking about the way things are used and, more specifically, the way things are designed to be used.

As designers, artists, makers, builders, we make things that are of use, in one way or another. At the same time, we make use of the productions of others. We do both of those things on an almost constant basis, in our lives, our vocations, our work.

A graphic designer may design a poster that serves the use of informing viewers about that which it promotes. That same designer uses a set of tools, however diverse, to fashion the poster. Thus, the builder is built for. Both the poster and the tools of the designer have affordances and potential use cases. What, after all, is the proper use of a poster? Is it to be read? Is it to be attractive? Is it to be taken off the wall and folded into a paper airplane?

Our software tools, in their affordances and potential use cases, define for us, to a certain extent, what we may and may not do. Those decisions are put in place by the people who design the tools. Together, as users, developers and all areas between the two extremes, we boil in a constantly reconfiguring sea of use possibilities, material and mental affordances.

Which is why, in issue 1.2 of Libre Graphics magazine, we're looking at the interconnecting topics of use cases and affordances. We can look at it from a technical perspective but, perhaps more productively, we can also look at it philosophically. It's about the idea of the affordances of the work, who it's for, what it can do.

That applies both to the work designers do for others and also to the work of others, as it is employed by designers.

Use, mis-use and happy accidents are all areas to be discussed and explored. We're talking, this time around, about all these things. And we want your contributions.

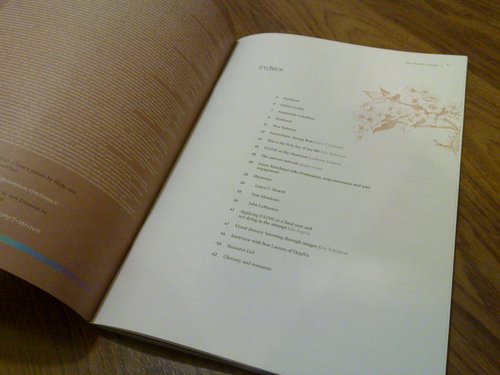

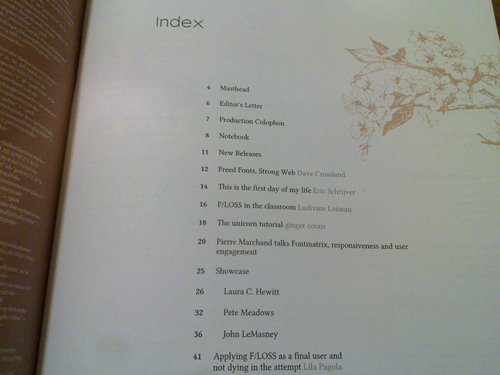

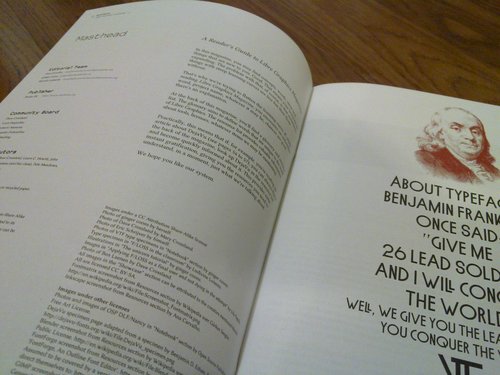

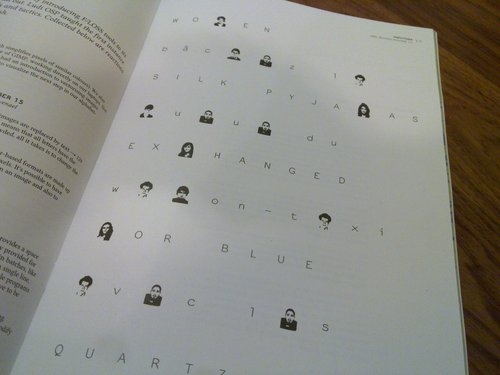

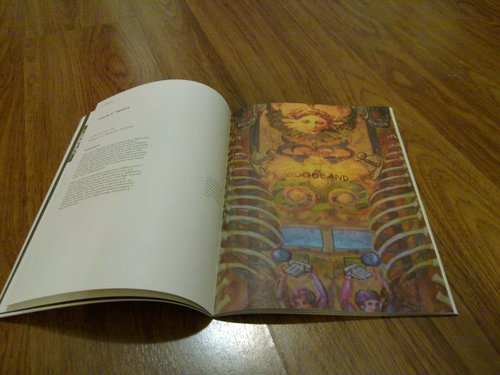

Libre Graphics magazine is seeking submissions for issue 1.2, Use Cases and Affordances. We want your written or visual work, created with Free/Libre Open Source tools, methods and standards. Flip through issue 1.1 to see what we've done in past, then propose to do it again, or better, or to do something else entirely.

Submissions to submissions@libregraphicsmag.com

Submissions for this issue are due by 11:59PM EST, 15 January, 2011